Translated by Justin Loke (1 April 2014)

One afternoon in 1967, the author of this article witnessed the following scene: Borges, who had traveled to Santa Fe to speak about Joyce, was chatting animatedly in a café with a small group of young writers who had come to interview him before the conference. All of a sudden, he recalled that in the 1940s he had been invited to join a committee that intended to translate Ulysses collectively. Borges said the committee met weekly to discuss the preliminaries of this monumental task, which the best anglicistas of Buenos Aires were preparing to undertake. But one day, after nearly a year of weekly discussions, one of the members showed up brandishing a massive book and exclaimed, “A translation of Ulysses, just published!” Borges laughed heartily at the incident, and even though he had never read the translation (and probably not the original either), he concluded: “And the translation was very bad.” One of the young writers listening replied, “Maybe, but if that’s the case, then Señor Salas Subirat is the greatest writer in the Spanish language.”

This response reflects the attitude toward translation among young Argentine writers during the 1950s and 60s. The 815-page book had been published in 1945 by Editorial Santiago Rueda of Buenos Aires, which also released A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in a translation attributed to Alfonso Donado (read: Dámaso Alonso). The publisher’s catalogue also included major authors like Faulkner, Dos Passos, Svevo, Proust, Nietzsche – not to mention the complete works of Freud in 18 volumes translated by Ortega y Gasset. In the late 1950s, these books circulated widely among those interested in literary, philosophical, and cultural issues of the twentieth century and were essential holdings in any serious library.

The Ulysses by J. Salas Subirat (the initial “J.” giving his name a mysterious aura) often came up in conversations, woven into the endless stream of speculative discussions left deliberately open-ended. Anyone between 18 and 30 with a passion for narrative in Santa Fe, Paraná, Rosario, or Buenos Aires knew the book by heart and could quote it line by line. Many writers of the 1950s and 60s learned much of their narrative technique and acquired many of their resources from that translation. The reason is simple: the turbulent current of Joycean prose, rendered into Spanish by a man from Buenos Aires, carried with it the living energy of spoken language, something that no other author, except perhaps Roberto Arlt, had used with such ingenuity, precision, and freedom. The lesson was clear: the language of everyday life was the source of energy that nourished the most universal literature.

Although it was the first translation, its merit may not lie solely in intrinsic quality. Still, it is vulnerable to two opposing but related dangers: biased criticism and intellectual pillaging. This has long been the fate (though some are beginning, albeit reluctantly, to correct it) of Salas Subirat’s extraordinary effort. It is unacceptable that the translator of a second version of Ulysses into Spanish would claim ignorance of the first. Yet this seems to have been the stance of Professor Valverde, who offers justifiable praise in the 46-page preface to his version, which was published by Dámaso Alonso, but says nothing about Salas Subirat’s translation. A comparison of the two reveals that Valverde’s silence likely stems from an obsessive desire not to resemble the earlier version. No serious translator of Ulysses today can ignore the first and second versions, this is the honest approach adopted by Francisco García Tortosa and María Luisa Venegas in their third translation, and such acknowledgment means that all translations become necessary reference points. However, Valverde’s version appeared with a kind of disdainful righteousness, as if it had arrived to correct the supposed ineptitude of the first. On the internet, natural homeland of the absurd, one finds not only various misrepresentations of Salas Subirat’s translation, but also a commercial travesty: the 1996 “massacre” by a man named Chamorro, who claimed to have corrected “up to 50%” of the original version. He criticized, among other things, its use of Buenos Aires colloquial speech, as if a Londoner translating Ulysses would have stripped Dublin slang in favor of Oxford English. This act of piracy, fifty-one years after the book first appeared, leads one to observe that “it is, in some ways, merely a repetition of Salas’s translation.”

Writer Eduardo Lago has compared the three authentic translations (wisely excluding Chamorro’s act of vandalism), and he does not award any one of them a perfect score – and rightly so. It would be rash to claim that any version is definitively superior. Lago’s comparison is impartial and meticulous, and his close reading of different passages shows what was already evident in the first two translations: that the authors managed, with relative success, to resolve the challenges of the original. The purpose of a translation is not to show off the translator’s erudition or mastery of the source language, though both are certainly required, but to integrate the original into the living language of the target culture. In every era and every linguistic field, new translations of classics are necessary. But this need should not entail the denigration of earlier versions.

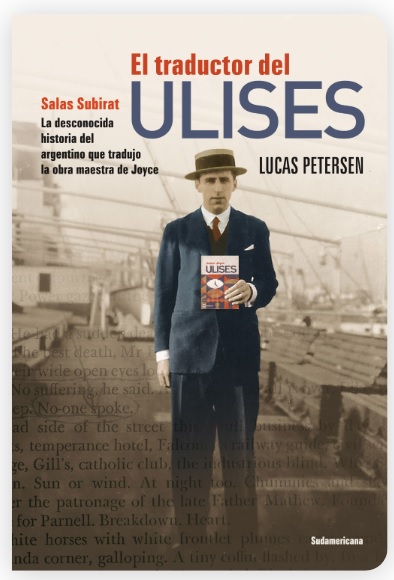

José Salas Subirat, neither Catalan nor Chilean, as some vague reports in literary journalism have claimed, was born in Buenos Aires on November 23, 1900, and died in the town of Florida on May 29, 1975. He is buried in the Olivos cemetery. He was self-taught and worked, among other things, as an insurance agent, even writing a professional book titled Life Insurance: Theory and Practice. Information Analysis was published in 1944, just a year before he completed his Ulysses translation. In the 1950s, he also published self-help books like The Struggle for Success and The Secret of Concentration, and an open letter on existentialism that James Wheel included in his catalogue. But he had also written social novels, poems (Signalero), and articles for anarchist and socialist publications during the 1930s.

Published in the supplement “Babelia” of El País (June 12, 2004)

http://elpais.com/diario/2004/06/12/babelia/1086997822_850215.html

For a detailed portrait of Salas Subirat’s eccentric life and unlikely role as Joyce’s first Spanish translator, see Lucas Petersen’s article in The Irish Times: “José Salas Subirat, the eccentric first translator of Joyce’s Ulysses into Spanish”. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/jose-salas-subirat-the-eccentric-first-translator-of-joyce-s-ulysses-into-spanish-1.3951644

.

Leave a comment