The Complete Turn

Ñ Magazine, Clarín, Buenos Aires, December 20, 2003 (published in Una Forma Más Real Que La Del Mundo, Primera Edicion, Manslava, Coleccíon Campo Real, Buenos Aires, 2016)

By Fernando García

Juan José Saer has lived in Paris since 1968, but all his work refers to a region in the Santa Fe littoral. Ñ followed the great writer through the geography of his fiction and previewed scenes from La grande, the ambitious novel he is currently preparing.

—Old men here, to be able to make love, have to pay. I think capitalism exists because no one wants to sleep with an old man. It seems like a joke, but it’s not. There’s a whole reasoning…

—What is it?

—Power is economic and sexual. And sexuality is practiced by young people. Ensuring the survival of sensuality also means ensuring money. The rich want to be rich because no one wants to sleep with an old man. Charles Fourier said that young people had to follow “angelism” and give themselves to the elderly as a reward for having brought society into harmony.

—Call it what you want, but you have to think about how changing the conditions of material existence changes consciousness.

—A utopia…

Saer delivers his erotico-Marxist sermon while we walk a path below a cliff on the Santa Fean shore. Now it’s noon on a cloudy and dense day, the dawn of a storm that wreaked havoc in the surroundings of Santa Fe, and Saer points with his finger to a horizon on the shores of the Colastiné River, all muddy and with camalotes floating upstream, drifting backward. Like the repentant.

“Over there, look, where you see that cluster of acacias, that’s where the Tiradero stream is.” It’s a name with enough picareque octane to establish comic frequency with the 66 years old. Some say the Tiradero brings with its sudden scenes of youth and “skirmishes” beneath the acacias. Thus, that fragment of a haphazard conversation became a delicious Saerian introduction to visit that place, the Colastiné River, a Santa Fean midday, one of the stops suggested by the writer to revisit the mythical locations of his writing.

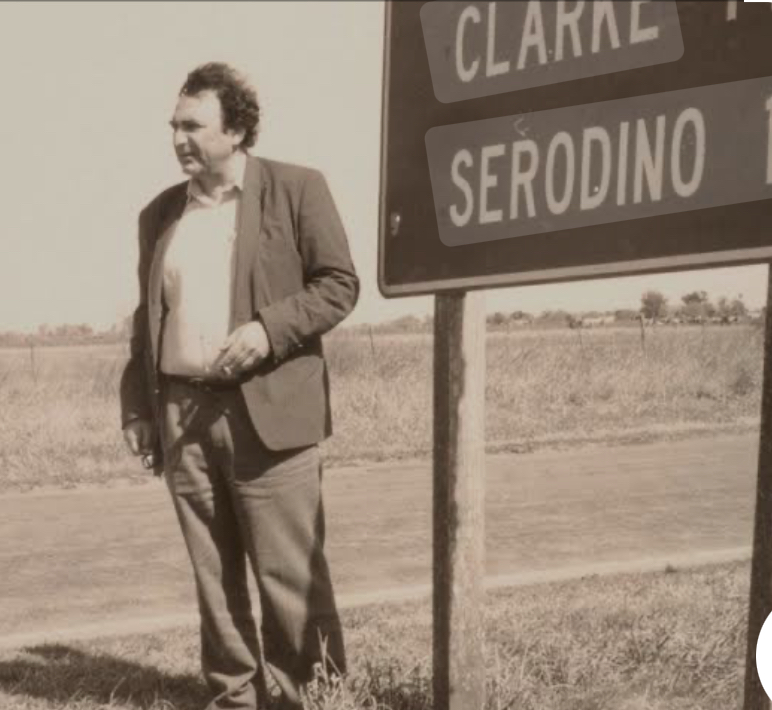

We must explain this safari with Saer. We came to Santa Fe, crossing a tornado that left thirteen dead near Rosario, to travel, along with the writer, Colastiné, Playa Rincón, Santa Fe, and Serodino. A whole day touring the landscapes of his life and fiction. And later, the return to Buenos Aires, on the route with one of the best drivers in Argentina.

Saer has lived in Paris since 1968, where he settled to teach literature at the University of Rennes. Since then, he has written fifteen unique books that blend and subvert the rules of the novel, poetry, and essay. That part of the “Saer catalog,” written in Paris, with those small hands performing images and sensations that always end up being here and now: an arm of the Paraná River, the humid and thick juice of coarse sand, and Saer shines, like in a mirage, characters trapped on the shore of the Santa Fe littoral.

Since retiring as a professor in Rennes, Saer has been planning what he says will be his most extensive and ambitious novel. He knows it will be called La grande and will write it in Paris (“I will never live in Argentina again,” he insists), but the future words are already here, on the banks of the Colastiné River, two pesos for the peaje (toll) to a big-bellied, tattooed local with an ominous gash on his abdomen.

“See, more or less this is how my new novel begins,” says Saer, narrowing his gaze like a filmmaker on a set. “There’s this river, the sky with heavy clouds like these, this heat and small waves formed by the sudestada now. Well, maybe make the waves a bit bigger.”

Saer is back, in the laboratory of his sensations and emblematic places, collecting the beginning of what will be, he says, one of his most awaited books. He does it and points to things from Santa Fe as if they were arranged on a maqueta (scale model), like those used by architects. He is also there, in some way seeing himself, a little figurine. Saer is made of all his stories and characters.

On the way to this little beach, twenty minutes from downtown Santa Fe, he had already hinted at this capacity to make what we saw from the the window of the hired car, a mirror filtered through his imagination and experience. A spiritual and imaginary guide of the Santa Fe littoral. We leave behind the ring road that leads from Santa Fe to Paraná and Saer, at that moment, points out something in front of a gigantic shopping mall that’s just been built, now passing on the right side of the car window. There.

“There it is: the colossus of the swamp.” One looks and sees a shopping mall, one more, bah. But no; it’s Saer’s machine at work, el coloso del pantano.

“I plan to include the colossus of the swamp in my new novel. You won’t believe it, but underneath that shopping mall there’s a massive swamp. If you could still see it, look over there, there…!” The same goes for that inexpressive part of the river now turned into another bright signpost on the Saerian safari. That spot which is “the real lemon tree place,” his great novel of 1974, as he says.

Or across the street, that light-colored horse that walks around while Saer enjoys the silence. “Look, a white bay like in Nobody Nothing Never.” And he laughs, mischievously, twisting his gaze under his glasses. “You’re going to think this is all set up for me, right? But no, no…” That’s how Saer is. He has written and is, in essence, all these things. And all of it finally seems to be a three-dimensional immersion in his books with the best possible guide.

LAS DELICIAS, DOWNTOWN SANTA FE

There’s Saer. It’s ten past eleven in the morning, the time he asked to meet at this splendid café Las Delicias in downtown Santa Fe. The idea was to chat for a while and plan the trip afterwards. Saer entered with his back to me and stood there trying to locate me in the middle of the café where, precisely, I am not. It takes him a few seconds, during which I decide to let him think he’s facing an invisible man. Saer is wearing the same outfit I saw him in back in Buenos Aires. Blue jacket, tea-colored pants, and a short-sleeved plaid shirt. His shoes look old. Saer, a son of Syrians who looks a bit like Alberto Sordi, never seems to have spent more time in Paris than here, on San Martín Street in Santa Fe.

This café of Viennese inspiration represents, for the writer, the architecture that returned this city to him through the eyes of a stranger, a thousand kilometers to the north. It was in a winery, in Paris, decades later, that an almost ancient Frenchman recognized Saer’s Argentinian identity and linked it to Santa Fe, first, and later to this place, Las Delicias, through the memory of “the lady on the hammock,” a myth anchored in some dance night between 1927 and 1937.

“I didn’t know the lady on the hammock but I found out she existed. They were the most beautiful sisters people in the city talked about,” says the writer.

He came to this city from the countryside ten years ago. In the 60s there was already a café here, but Saer, then a poet and a key contributor to the independent theater circuit, frequented another place a few blocks from this table we are at now, where he bites into a mil hojas (“a thousand leaves” pastry). “Mil hojas! This is a Santa Fe-style alfajor, a real panzer of breakfast. Cultural appropriation!”

His favorite was the gallery café, the first gallery that existed in Santa Fe, always known simply as “the gallery.” It’s impossible not to imagine the ghosts/characters of Saer at that bar: Tomatis, Barco, Leto, Garay, the Mathematician, and those women of devastating irony who populate his writings. All those creatures, names Saer pulled from the general store of his family in Serodino, have been, and still are, every time someone reads, walking down this very San Martín street that Saer looks out on from the tables of Las Delicias.

I tell Saer that many of his readers imagine that these characters live, breathe, love, are real men and women that he encounters on each journey like some sort of secret spring. That they ask themselves, for example, if Carlos Tomatis, his supposed alter ego or at least his favorite character in his stories and novels, is in fact Saer. Is he?

“Not at all,” Saer interrupts. “Many people have asked me that. All the characters have something of me and something that doesn’t. Tomatis has many elements of mine, as do other characters, even female ones, who have them too. Fiction contains autobiographical elements but its only goal is fiction itself. Look: in my new novel, Tomatis has a whole theory about Oedipus Rex. That’s his, not mine. I don’t have any theory.”

— Come on, you’re the one who writes the words…

— “I don’t treat a text as something tangible, and the same goes for the characters. We don’t know people in a linear way like we know ourselves in the novels of Isabel Allende, from beginning to end. I tend to sketch out the explanations. Even though many of my stories are composed in clear lines, speaking in terms of plot. But that clear line is never sufficiently explanatory in terms of the storyline. I try to give everything I write a certain opacity.

—Aren’t you afraid of hermeticism?

—No. I don’t do it out of whimsy, to exclude the reader, but because that’s how I perceive the world. My brother died three years ago and I swear there are things that can’t be said. I want to convey that. That’s why my stories always have an open ending. I call it “the poetics of disappointment.” I believe that opacity, which we inherited from Joyce and Kafka, is part of the art of the 20th century. We find it in painting, music, in a series of phenomena explored in that century.

Later, at dusk that morning, at 160 kilometers per hour, on the return to Buenos Aires, he insists that his characters carry a peculiar anguish, which is composed of a murmur of the era that still endures in its modes. Thinking of the angelic losers of the beatniks, Saer says of them, and yes, they are the ones in the books and also the others, the ones from San Martín Street, the ones you can imagine sitting next to young Saer at the bar. “I mean the misfits. I myself never quite fit into the literary environment or the academic one. And that goes for everyone I know here, doesn’t it?”

The trip with Saer, then, had begun at the door of Las Delicias. Then Colastiné, Rincón, barranca of Saerian barbecues, where we lost our way for good with Saer directing the remís (car with driver) in the opposite direction, the Santa Fe riverbank and, afterward, setting course for Buenos Aires, Serodino, the place where he was born. Places within reach from San Martín Street but also in Paris, waiting to be rewritten and repopulated by the team of Saerian misfits.

Characters who never, but really never, went French. A mystery, isn’t it? Just like Saer’s accent, which doesn’t carry even a hint of French inflection. “It’s the job that causes me the most problems, I have to monitor it all the time. It’s a concrete and conscious vigilance: the barrier against Gallicism,” he would say.

SERODINO–BUENOS AIRES

“I don’t recognize anything, how much this has changed.” The car enters a street in Colastiné, kids pass by on their way to school, and Saer thinks aloud about this town, his last Argentine residence before settling in Paris. It’s here, in any case, the little pink house and “the furnished motel” where Saer and his wife Bibí Castellaro lived and worked. The abandoned motel can now be rediscovered as a magnet of literature, it appears in the novel La vuelta completa. And in the bucolic tale that Saer evokes: “We used to run the motel. One night Ortiz came to visit, who was a close friend of the owner. That night we took over the motel with friends. Imagine the scandal if the police had come: Juanele Ortiz and I in one bed, two minors in a mueblada, would’ve been a huge mess.”

There is much more to Colastiné, though Saer is ecstatic with the walk. A sulky passes by and I think about the distance between these Santa Fe marshes and the zone where Saer lives in Montparnasse, Paris.

—And you left from here to Paris, non-stop?

—Yes.

—And?

—It’s a big change!

—Yes. There are no suburbs in Paris.

The writer recommends surubí (a native fish) next. He suggests we have lunch at the old Castelar Hotel in the city of Santa Fe, and he’s not wrong. In a short time, with the immaculate grease of the Paraná delicacy still on the palate, we pick up Saer at his sister’s house and take the Santa Fe–Rosario highway toward Serodino, on an afternoon undecided between rain and sun, before heading back to Buenos Aires. That evening, this same road was like one of the gloomy, Goyaesque landscapes that director Peter Jackson envisioned for The Lord of the Rings saga. A misty darkness stalking a fierce storm’s eye, all the beastliness the cosmos can show from here: the place, according to Darwin and Saer in The River Without a Shore, that’s the flattest on Earth.

Serodino. There’s an absurd toll, a straight road, the ghost of a small train station that closed in the ’50s, a boulevard, a nephew Saer doesn’t know. A white house, like others, that our guide reinterprets.

“On this sidewalk, I had a dream when I was five years old. I dreamed that my mother had died, that she was lying there and that there were angels playing trumpets to wake her up.” It’s the first manifestation of the subconscious that the writer recalls. And here it is.

The pavement ends. On the other side of the boulevard, there is a construction from the late 19th century, with weeds sprouting like hair on an old skull. “This was my house. With the storage room included, even though it’s been abandoned for years.” A photo? “No, let’s keep going, too many people here. I’d feel embarrassed. Let’s walk down this block, where no one knows us.” We walk, a few stray dogs follow us, we see the house of Saer’s grandparents, the Anoch bakery, things that are upside-down or maybe reversed, the old Serodino train station that once ran up to Tucumán, now dead. It’s now a library: Saer donated his books and journals. Someone opens the door and pops their head out: “Do you need something?” Saer says no, he just wanted to see it again.

Two hundred meters ahead, the countryside swallows up Serodino, like a toad swallowing an insect, and we’re back on the road.

We pass Arroyo Seco, Fighiera, Villa Constitución, Theobald, Ramallo. We pass Kirchner (“declaring oneself Peronist is impossible, but Kirchner is a model of overcoming”), the seventies (“I hated the Montoneros of the immediate left, they had nothing to envy of the more criminal right”), Piazzolla (“he wanted to make tango the continuation of baroque music. I like it only at the beginning”) and Borges (“I was one of the first to vindicate him from the left”).

We pass Rosario. “Let’s keep going. If we stop, we’ll have to visit the cabarets, to see the girls I used to see in my youth, in the hospice, of course.” Saer jokes, the car bursts into laughter. In a few hours, he’ll push open the swinging door of a hotel on Arenales Street, and who knows, maybe this dreamlike journey through the geography of his work will replay again.

There he goes, the man who swears that the end of capitalism, well, lies in the voluntary sexual union of the young and old.

Leave a comment