At times, reading Walter Benjamin, or reading about him, brings me back to that afternoon when she was cooking in the kitchen. The copy I had was from the school library. I remember a renowned local art historian, during some gathering, dismissively calling the library collection “wretched,” unaware, perhaps, that John had asked the library to purchase a catalogue of books covering important titles in the critical theory lineage.

The paperback I borrowed, and renewed, was wrapped in a needless plastic sheet that had yellowed slightly with time. In Singapore, it’s common for schoolchildren to wrap their textbooks in transparent film – surely a decision made by their parents – and I remembered how, back then, seeing a classmate without that protective layer made their book seem almost barefoot, if not semi-naked. This copy felt much the same. Its corners were worn and peeling, and every time I turned a page or shifted my grip, the cover gave off a faint, brittle crackle, like cellophane forgotten too long on the shelf. Not to preserve value, really, but as a kind of premature preservation, sealing the book like a baby embalmed.

Later I discovered those librarians used other, even more atrocious methods of preservation. There were two other kinds of covers I recall: one was a soft plastic jacket that slipped over the book like a second skin, but was crudely, untidily held in place with scotch tape, leaving marks ; the other was adhesive – a kind of laminate applied directly to the cover, smooth but prone to air bubbles if done in haste, and once hardened, left the book cover rigid and unbending, like a paperback trying unconvincingly to pass as a hardcover.

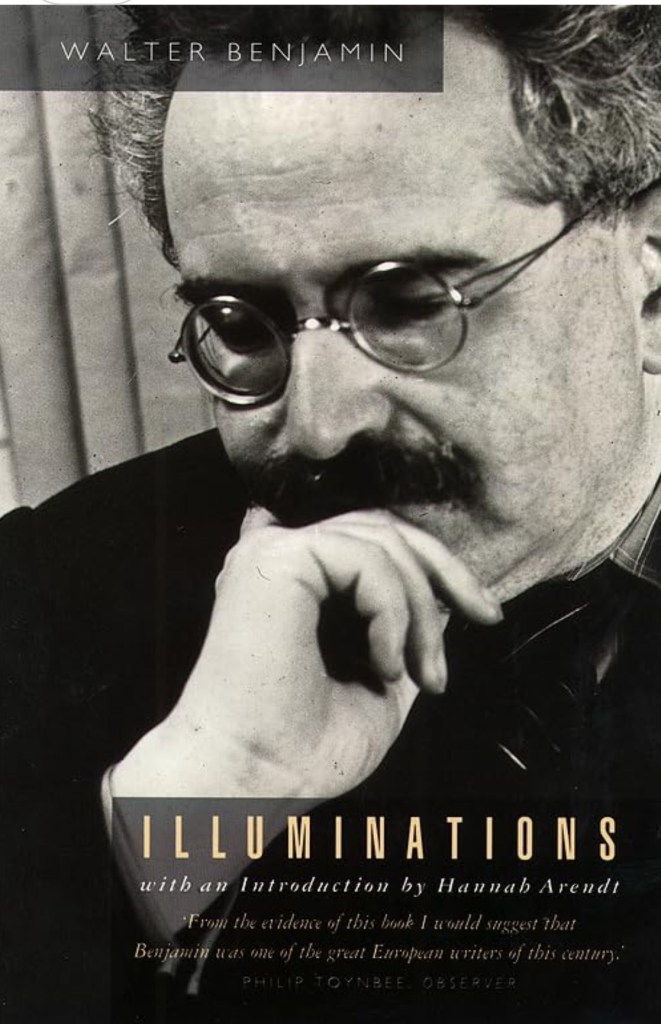

I think I was not even twenty-one then, and my language ability was nowhere near what it is now, at forty-five. The cover of Illuminations, the edition I held, had that familiar image of Benjamin ruminating, as though caught mid-thought. How much I understood of what I read is less important than the fact that I remember it still: the moment, the smell from the kitchen, the sense of something beyond my grasp but already part of me. I also remember the innocuous remark she made about me reading things beyond my abillity, but I’ve since realised that learning a language is not reading what is easy, but about following what draws you. That is the best motivation. It was for me then, and still is, as I’ve found again in learning Spanish and Chinese, and perhaps also in the disappointments of human relationships.

Leave a comment