Spinach as Pharmakon

At first glance, Popeye the Sailor seems harmless: a comic celebration of spinach, a cartoon moral about the virtues of healthy eating. Yet beneath its slapstick repetitions lies a darker structure. Popeye is not simply nourished by spinach; he is dependent on it. He cannot triumph without the can. Read allegorically, Popeye becomes less a parable of nutrition than of addiction. The figure trapped in a cycle of reliance, and consumption, his identity bound to a consumerist substance that both saves and enslaves.

In Plato’s Pharmacy (in Dissemination), Jacques Derrida shows how the word pharmakon means both remedy and poison, cure and toxin. It is a concept that unsettles the very opposition between health and sickness. Spinach in Popeye’s world plays precisely this role. It does not simply nourish; it alters him instantly, like a drug that grants superhuman strength. Each episode replays the same ritual: Popeye falters, consumes, and triumphs. The spinach is his pharmakon. What rescues him, but also what chains him to dependency.

The Cycle of Dependency

This cycle mimics the addict’s experience. Popeye delays spinach until the moment of crisis, then surrenders to it as the only solution. His victories, though spectacular, are temporary, erased by the next episode, when the same craving will return. The narrative itself enforces the addiction: there is no Popeye story without the spinach scene. The cartoon, like the addict’s life, becomes structured by recurrence.

Walter Benjamin, in The Origin of German Tragic Drama, distinguishes between the symbol, which seeks wholeness, and allegory, which lives amid ruins. In allegory, objects point not to fullness but to absence, to what is broken or irretrievable. Is Popeye’s spinach can an allegorical emblem? Does it stand for the absent strength he cannot generate within? Each triumph is temporary, collapsing as soon as the credits roll. Popeye’s life is not progressive but cyclical, suspended in the eternal return of compulsive consumption.

The Consumer of Hope

The irony lies in the choice of spinach. Addiction is usually linked to vice such as alcohol, drugs, gambling. But spinach is the symbol of health, a staple of childhood obedience. By cloaking dependency in the guise of virtue, the cartoon anticipates how modern culture often disguises addiction under acceptable forms: casinos as “entertainment,” drinking as “bonding,” workaholism as “dedication,” and of course, the seemingly harmless lottery presents itself as salvation, as hope incarnate: for the price of a ticket, the poor man may dream of wealth, the weary worker of escape.

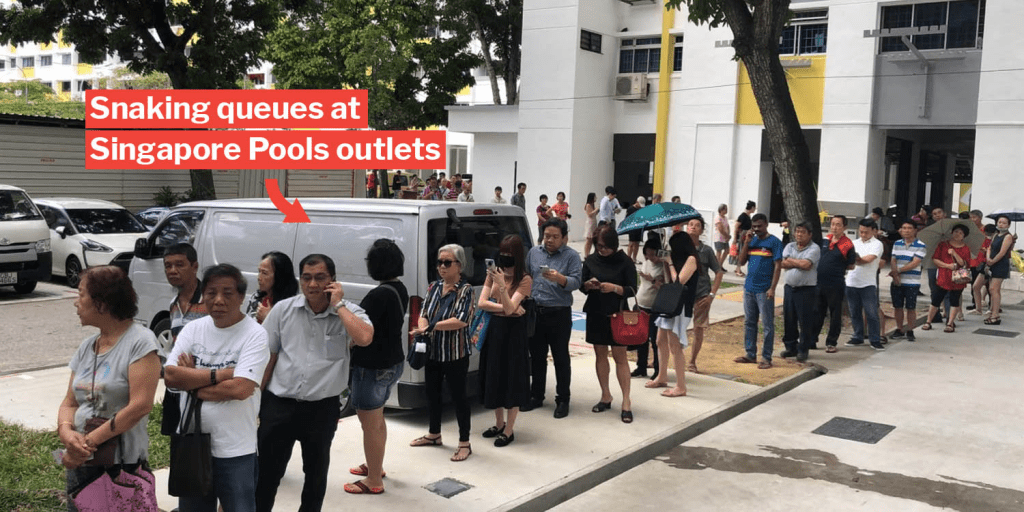

This marks the shift from the 19th century’s concern with depravity in the relations of production to the 20th century’s logic of consumerism, where alienation no longer stems only from labor and factory discipline but from cycles of consumption itself, of commodities, of images and desires on scoial media. What is consumed here is not merely a product, but hope, espera (waiting) and esperanza (expectation or hope), a secularized providence in which redemption is promised not by faith but by chance. Like Popeye’s spinach, the lottery is a pharmakon: it cures despair by offering fantasy, but poisons by entrenching the very conditions of desperation. The ticket, like the can, is allegorical. It is not a symbol of genuine salvation but a sign of absence, of the life deferred. Spinach, then, is the most insidious pharmakon because it is celebrated, while the lottery is a promise of redemption that perpetuates ruin. Hence, when there is huge snowball prize money of a huge amount in Singapore, we see a long queue similar to the soup kitchen in the West, or unemployed waiting for a job.

I was reminded of a lost photo, few year ago, before Milei became Pressident, a friend sent me, when visiting Argentina, photo of unemployed people queueing for a job in the morning. I was reminded of some of the scenarios depicted in Roberto Arlt’s Aguafuertes almost a century ago.

Popeye without spinach is still himself, but weaker, mocked, incomplete. With spinach, he is invincible, but only for a fleeting instant. His sense of self is chained to the can. Addiction works the same way: the substance fuses with identity, until one feels powerless without it. What appears as empowerment is in fact enslavement; what looks like choice is only repetition. Through this lens, the comedy of Popeye shades into tragedy. His victories are prefabricated, dependent on the ritualized fix. He is condemned to repeat: to falter, to consume, to triumph, to repeat again. The sailor, whose forearms bulge with strength, is at heart a fragile figure. His destiny is not freedom but compulsion, not growth but recurrence. Here, Popeye ceases to be a simple champion of vegetables. He becomes instead a figure of an allegory, his physical strength depending on spinach is the inversion of his soul in a vegetative state: a sailor forever denied freedom, caught in the loop of a dependency disguised as virtue.

Is the figure of the sailor, in seafaring narratives, not the final attempt at redemption in the history of the proletariat? The recurring gesture of those who, having squandered or broken their lives on land, fled to the sea? Sailors, in this sense, embody a flight from failure as much as a search for fortune.

I once read that conquistadors like Hernán Cortés, too, sought in distance, via the sea, a redemption no longer possible at home. Many were in similar straits: lesser nobles, unemployed soldiers, or men crippled by personal debts. Exploration and conquest were imagined as a gamble for salvation, a wager to restore fortune and honor. To finance their participation, they borrowed, pawned possessions, or promised creditors a share of future plunder. Cortés, of course, was no worker but a younger son of a hidalgo family, from a region that produced many conquistadors. Without inherited land or wealth, and often entangled in debt, often for a variety of bad reasons, he sought both economic survival and social advancement by crossing the ocean.

In truth, these men were sailors by necessity and conquistadors only by contingency: it was the accident of finding treasure or other civilizations to plunder, the sudden license to kill and to conquer, that transformed them into figures of conquest for God, Glory, and Gold.

From Popeye, the sailorman with huge, disproportionately muscular forearms, his spinach-can inventory and strength, I started to digress, I thought of sailors in general, and of the salty breeze by the sea. The figure of the sailor an existential wager, a body fleeing the land it has exhausted.

I am reminded of Mallarmé’s Sea Breeze::

The flesh is sad, Alas! and I’ve read all the books.

Let’s go! Far off. Let’s go! I sense

That the birds, intoxicated, fly

Deep into unknown spume and sky!

Nothing – not even old gardens mirrored by eyes –

Can restrain this heart that drenches itself in the sea

O nights, or the abandoned light of my lamp,

On the void of paper, that whiteness defends,

No, not even the young woman feeding her child.

I shall go! Steamer, straining at your ropes

Lift your anchor towards an exotic rawness!

A Boredom, made desolate by cruel hope

Still believes in the last goodbye of handkerchiefs!

And perhaps the masts, inviting lightning,

Are those the gale bends over shipwrecks,

Lost, without masts, without masts, no fertile islands…

But, oh my heart, listen to the sailors’ chant!

(trans. A. S. Kline)

It is here where escape itself could be the cure, even if the cure is shipwreck. The sailor, like the gambler, consumes hope as his only commodity. Popeye’s spinach, the lottery ticket, the lifting ship anchor: each a different face of the same pharmakon, offering salvation through the possibility of ruin until one admits that no spinach, no lottery, no sea-voyage redeems, except the resurrection, the true Second Coming. It is not an issue of waiting or having hope, but of the means.

Perhaps it is not in all the men mentioned above that we find the right approach, but in a woman who knew how to wait: Simone Weil. In her French, attente means waiting in the deepest sense, a state of attention, receptivity, openness. It is not passive idleness but an active, watchful stillness. For Weil, attente de Dieu (waiting for God) is the stripping away of illusions and false consolations, holding oneself empty so that grace may arrive freely, without being forced.

Leave a comment