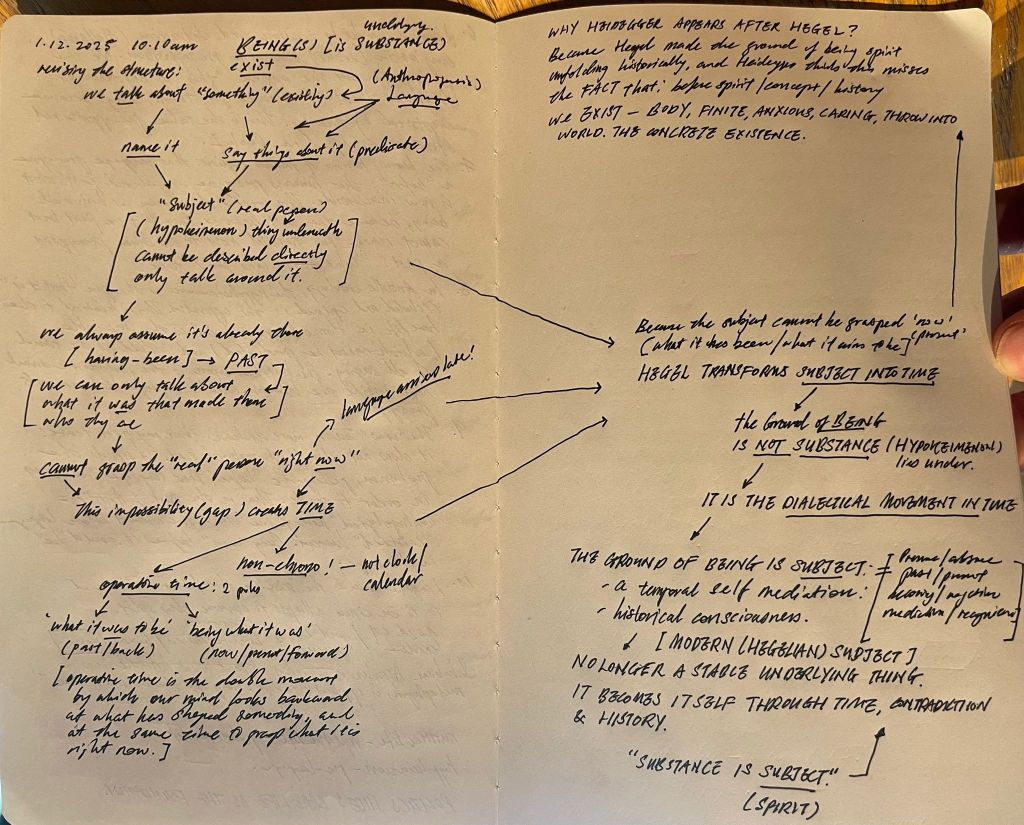

Whenever we speak about a person or a thing, we unknowingly perform two moves. First, we name it (“Katie,” “this person here”), which singles it out. Second, we say something about it (“she is kind,” “she is tall”), which assumes that there is already a stable “someone” underneath our words.

Aristotle

Aristotle noticed this and said: beneath all our descriptions there must be a subject (a “this-one-here”) that is already there before we speak. This hidden “underlying thing” is what he called substance. The problem is: this “real thing underneath” can never actually be spoken directly. You can only presuppose it.

Because language can never touch the real subject head-on, we experience it as something that has already happened. It becomes a “what it was”, a past, something already formed before speech. This simple gap, between the person we talk about and the real person we cannot grasp, quietly creates our sense of time. The present moment always runs slightly behind; who someone “is now” always echoes who they “were.”

Aquinas

Aquinas keeps this Aristotelian structure but adds a theological twist: what something is, its essence, comes from God, while its existence comes from being created by God. Essence and existence are not the same. This doubles the gap. A thing is what it is, but only because it has received its being from elsewhere. This reinforces the idea that the true core of a person is both prior and unreachable, known only “in the divine light.” So Aquinas deepens the sense of an underlying subject that cannot be fully articulated in language.

Hegel

Hegel turns this whole structure inside out. He says: the “subject” is not a stable thing hidden under our words, it is a process, something that becomes itself through time, contradiction, and self-reflection. What Aristotle treats as a fixed base, Hegel treats as a movement. The gap between what someone is and what they were is not a problem, it is how consciousness itself unfolds. For Hegel, the subject is this unfolding: a living story, not an inert support. Time is no longer a side-effect of language but the very medium in which the self becomes real.

Heidegger

Heidegger then enters after Hegel because he realizes something deeper: the entire history of Western thinking—from Aristotle to Aquinas to Hegel—has taken for granted that being must be grasped through this subject–predicate structure, where something always lies underneath what we say. Heidegger tries to step outside this heritage. He argues that our sense of time comes not simply from grammar, nor from a theological essence, nor from Hegelian history, but from the way being shows itself and withdraws, always partially hidden.

In other words, for Aristotle, the subject is the hidden thing underneath; for Aquinas, its essence and existence come from God, deepening its hiddenness; for Hegel, the subject is not a hidden thing but a temporal process. In Heidegger:,the very attempt to ground being in subjects or substances is the problem; time arises from how being reveals and conceals itself.

What ties them all together is this simple human reality: when we speak, the real person slips slightly out of reach.

We can only describe them through what they have been, through traces and stories. This small slippage, this impossibility of grasping the “pure now”, creates the line of time we live inside. Our sense of identity, memory, and history all originate from this gap.

In short, naming gives a unique individual, speaking about them presupposes a hidden core, this core cannot be spoken directly, so it becomes something “already past,” and this “already past” becomes what we experience as time.

[The ancient Greek philosopher identified what lies under, a theologian deepened the substance in relation to God, a Prussian philosopher who saw Napoleon in Jena – Weltgeistes zu Pferde – turned it into a dialectical historical process, and the German (related to the Nazis, unfortunately unlike how Aristotle was related to Alexander the Great) tried to explain the ground that makes all of them think this way.]

Giorgio Agamben ties the entire chain together. For him, this split produced by language, between what something is and the silent subject we must presuppose, creates a gap that can never be closed. That gap becomes time, and time becomes the way we understand ourselves as beings with a past, a becoming, a story. This is why he calls it an ontological apparatus: language itself generates the subject by pushing it into time and forcing life to be narrated as “what it was to be.”

And this is also anthropogenesis: the human emerges at the moment language divides us from ourselves, when the spoken “I” and the silent, unreachable subject no longer coincide.

We become human precisely in the fracture that makes us historical beings, always interpreting who we are through what we have been.

Leave a comment