“It is not because life and death are the most sacred things that sacrifice contains killing; on the contrary, life and death became the most sacred things because sacrifices contained killing. (In this sense, nothing explains the difference between anitquity and the modern world better than the fact that for the first, the destruction of human life was sacred, whereas for the second what is sacred is life itself).’” – Giorgio Agamben, *Se, p.136, Potentialities

I first read this passage of Agamben back in 2011, when I was in Melbourne for about a month. I used a pencil to draw faint vertical lines on the brick wall of where I was housed, counting down to the day I would leave (not knowing what was to come over the next ten years of my life after I left Melbourne). It was a private joke between me and my roommate, the same person with whom I drank cheap supermarket white wine that cost less than bananas.

More than a decade later, I still cannot say I have fully understood the passage. But each time I return to it, one idea continues to unsettle me: life and death are not sacred because they are precious; they became sacred because sacrifice contained killing.

Before encountering the passage, I assumed, like most people, the opposite. I thought ancient people considered life inherently sacred, and that is why they ritualised and protected it. Agamben turns this upside down. In antiquity, it was precisely through killing, through the ritual destruction of life, that the sacred appeared. Sacrifice did not protect life; it made life meaningful by destroying it in a consecrated way. Killing was not simply violence; it was a divine transaction.

This explains something essential about the ancient world: the destruction of human life could itself be a sacred act.

Modernity is the exact inversion. Today, life itself is sacred, individual, inviolable and to be protected at all costs. If antiquity sacralised life through its destruction, modernity sacralises life through its preservation. Agamben captures this contrast with clarity: in antiquity, the destruction of human life was sacred; in modernity, what is sacred is life itself.

I relate this inversion to the disturbing figure of the man who can be killed but not sacrificed.

He belongs to neither world. In antiquity, killing him is not murder because he stands outside the civic order. Yet, absolved from murder, his death is also not sacrifice because it carries no ritual value. His death has no meaning, neither legal nor divine. He is the one who can be killed but never consecrated, who is exposed but not redeemed, who is alive yet abandoned.

What strikes me most is how Agamben links this ancient figure to our modern world. I need to memorise it like how people used to remember phone numbers: antiquity gave life its sacred meaning through sacrifice, and modernity life itself is sacred. To remember in my own words: sacrifice gave life its sacred aura in antiquity. The disappearance of sacrifice made life itself sacred in modernity.

Writing these notes is a reminder to myself that Agamben is identifying a structure that still operates today, wherever people are excluded, detained, dehumanised or rendered killable without consequence.1 The sacred is not an inherent property of human life; it is the shadow cast by the political decisions that determine what kind of life counts. And yet, even as I try to articulate this, I feel I am saying too much and too little at once. The confusion remains, and phone numbers are not remembered with variations unless it is a futile attempt to recall the forgotten number I had not dial for years. Others I remember by heart, but no longer recall whose they are.

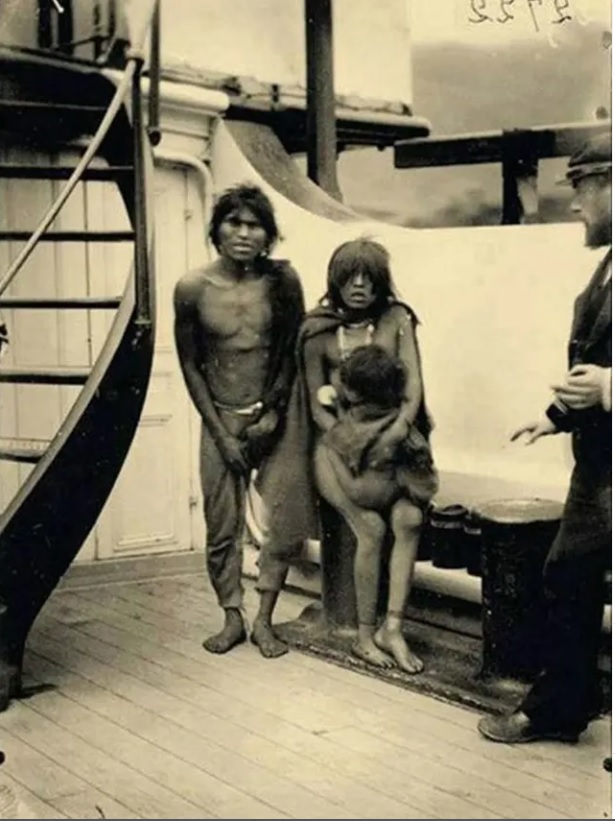

- Photograph: “In 1889, eleven Selk’nam natives, including an eight-year-old child, were taken from their homeland and sent to Europe to be displayed in Human Zoos. Stripped of agency, they were forced to perform, photographed, measured, and exhibited for public curiosity, treated as spectacles rather than human beings. The journey itself was brutal, and many perished from illness, exhaustion, or malnutrition.” from https://x.com/archeohistories?utm_source=ig&utm_medium=social&utm_content=link_in_bio&fbclid=PAZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAc3J0YwZhcHBfaWQMMjU2MjgxMDQwNTU4AAGnZNYF9W0rX8HpkY_7XdyP-JZ7iAAb1izMr2KeMIPzrJEUvFHlZgRp8xQv2HM_aem_uWVGrR-TTlcS9BllnC51Ug ↩︎

Leave a comment